Three Things for November 11, 2021

This week: New research from Pew looking at where Americans get their news. Also, the expanding audio news experience from publishers, plus smart speakers and concerns from across the pond.

THING ONE: Where Do Americans Get Their News?

The Pew Research Center published some new research1 this week exploring what platforms Americans use to stay informed about the news. The study looks at how consumption patterns vary by age, gender, race, ethnicity, and educational attainment.

Not surprisingly, the study reports that a large majority of U.S. adults (84%) surveyed say they often or sometimes get news from their digital devices2 followed by television at 68%, radio at 51%, and 34% of U.S. adults still relying on print publications3.

The more detailed topline summary also looked at how often U.S. adults regularly get news from various social media sites and podcasts. The results show a sizable drop with Facebook (36% in 2020 to 31% in 2021) with most other social media outlets remaining steady YoY. While still small in overall usage, the exception was TikTok, which doubled its results this year, with 6% of adults responding that they regularly get news through its website or app. In addition, the overall use of TikTok increased from 3% of adults in 2019 to 21% in 2021.

Since the growth of TikTok is being driven primarily by younger audiences, the Pew Study also divided up news platform usage by age groups, and you see where the digital natives (those between 18-29) are going for news. It’s also worth recognizing that nearly the same percentage of these younger audiences get their news, at least sometimes, from podcasts (33%) as they do from radio (35%).

What’s also interesting in the above chart is the relative strength of radio (52%) with persons aged 30-49 in comparison with television (58%) and social media (55%).

In addition to age, the Pew Study also looked out at news consumption across platforms by race and ethnicity, as detailed by the chart below. For example, 56% of Black audiences turned to radio as a platform where they get news. This is more than white (52%), Hispanic (44%), or Asian (40%) audiences that participated in the survey.

There was very little difference between these groups regarding podcasts as a platform for news consumption. The percentage ranged from 22% to 24% across the four different groups.

The study also drilled down to ask what platform would they prefer to get their news from, with half of all respondents choosing news from digital devices as their first choice. When asked a specific platform, 36% of U.S. adults said that television was their first choice, followed by news websites or apps (24%). Radio was only the preferred choice of 7% of those surveyed, and only 4% said podcasts are the platform of choice.

There is a significant disparity for news platform preference by age group that came out of the research:

Those between 18 - 29 years of age preferred social media (29%) ahead of every other platform. Only 12% of those between 30-49 had a similar preference.

Television was the first choice for those ages 65+ (57%) and between 50-64 (48%).

News websites or apps were the preferred choices for persons between 30-49.

Radio was preferred by 8% of adults between 30-49 and between 50-64. However, only 5% of those between 18-29 and 65+ chose radio as their preferred platform for news.

Finally, and I think this is really interesting, 9% of persons between 18-29 selected podcasts as their preferred platform for getting the news.

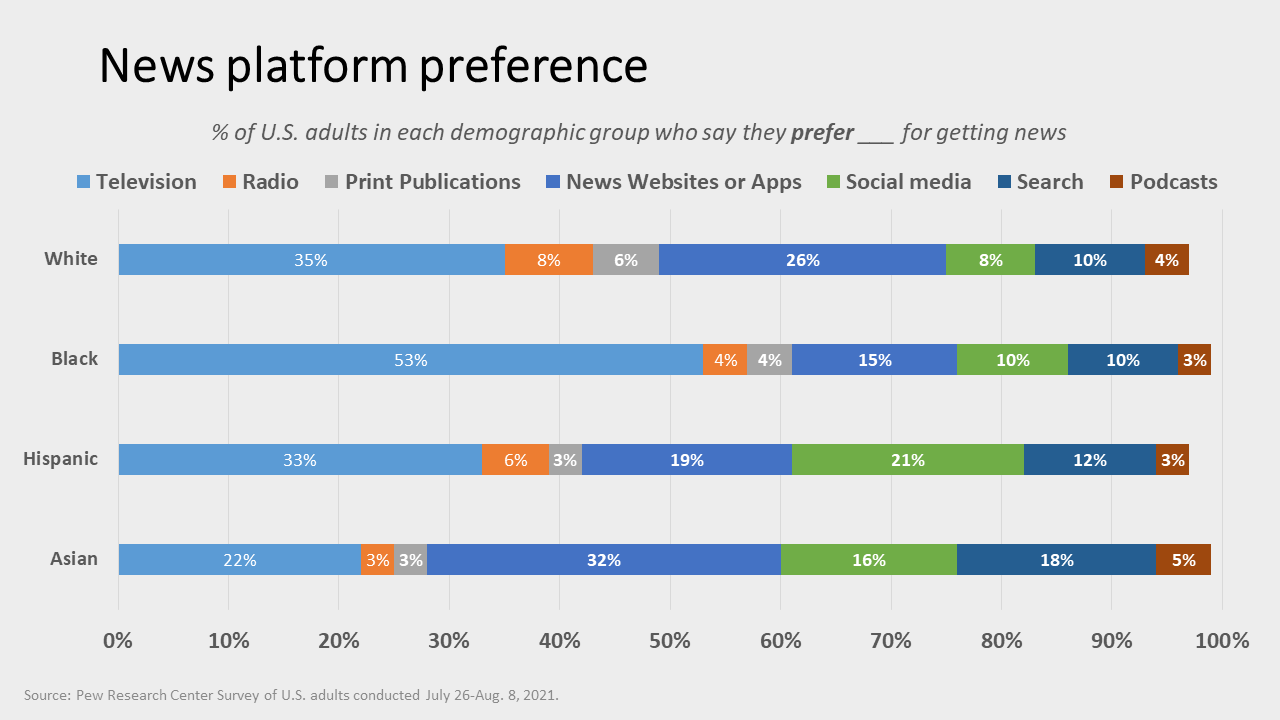

The above chart looks at the same question by race and ethnicity. A couple of things jump out to me from this data:

Black news consumers strongly prefer television (53%) as the platform of choice for news.

The preference to use social media was highest (21%) among Hispanic audiences.

News websites (32%) were preferred by Asian audiences ahead of other platforms.

The study also detailed news consumption across platforms by gender, educational attainment, income, and political leanings. The results from this research further reinforce the role that digital platforms play in terms of news consumption, particularly highlighting the generational divide that exists across platforms.

I also believe that the study doesn’t drive a nail into the coffin that radio is a dying platform for serving audiences with news content. However, it should serve to further push public radio to focus on strategies to serve audiences where audiences are headed, and that, of course, is on digital platforms4.

THING TWO: Expanding the Definition of the Audio News Experience

As the Pew study looked at different platforms for news consumption, it’s difficult to assess how it would define audio news consumption that doesn’t necessarily fall into the categories of radio or a podcast.

Over the past few years, a growing area of interest for publishers has been to add audio versions of their stories to their websites. Last year, The New York Times acquired Audm, the subscription-based audio app that offers listeners long-form journalism, read aloud word-for-word by audiobook narrators. When The Times announced its new audio app last month, content via Audm was highlighted as one of the standout features of the new product that will be rolling out soon in private beta for iPhones.

Publishers ranging from the Harvard Business Review to The Economist have been experimenting with adding audio versions of their stories to their sites for the past several years with the goal of expanding audience and retention for their publications.

The articles are closer to listening to an audiobook, usually featuring just one voice and no outside sound or music. However, publishers have found that the experiment has helped grow subscriber loyalty, reducing churn with their publications.

Up until now, most of the focus on this front has been to drive loyalty that would result in subscription revenue. That may be changing, though, as last week Digiday reported on some experiments taking place at two of McClatchy’s publications, the Sacramento Bee and the Miami Herald, to insert audio ads within the audio reading of the story.

The Digiday story reports that “click-through rates on the audio player have ranged from 1-5% across McClatchy’s pages, depending on the length of the story and the section of the paper they’re in, a scale promising enough that McClatchy’s sales team has begun to tuck ads in.”

Last month, the sales team ran its first campaign, which featured both pre-roll and mid-roll spots; the mid-roll ads had a completion rate of 75%, and the pre-rolls over 99%.

Though McClatchy’s sales team is still figuring out the optimal way to package and sell the spots — “We’re still figuring out that go-to market strategy,” said Rachel Malpeli, director of digital solutions at McClatchy — the hope is that the audio content can help add a new dimension of engagement for its readers and advertisers. “We want to really localize it,” Malpeli added.

That last quote from Malpeli should get the attention of the radio industry.

The audio ads that McClatchy is selling are being offered as a standalone product - I heard an ad for Home Depot attached to one story as an example. They are also packaging them with other digital products because of the limited scale of the product at present.

If other news publishers see the opportunity to generate advertising revenue by converting text to audio, it creates a more crowded space for public radio in terms of its share of listening and acquiring sponsorship revenue.

Public radio veteran Gabe Bullard, now the Deputy News Director at WAMU, wrote a very thoughtful piece for Nieman Reports last year about how audio articles are helping news outlets increase the loyalty of audiences. It goes deep about what publishers are trying to accomplish in this space.

One of the big takeaways from his piece is that “narrated articles may not offer the most robust listening experience, but they do offer one that’s convenient for listeners.”

In the battle over the Share of Ear, public radio needs to pay attention to this growing trend from local publishers as they seek to find new ways to connect with audiences and then monetize those relationships either by subscriptions or advertising.

THING THREE: Smart Speakers Adoption, the U.K. Government, and Radio

Over the months of writing this newsletter, we’ve explored the state of the smart speaker market as an opportunity to maintain in-home listening to audio as fewer Americans have functional AM/FM radios in their home.

Kagan, a research group within S&P Global Market Intelligence, is projecting a 12% increase in worldwide shipments of the devices in 2021. With the holidays approaching, we should expect a lot of advertising from Amazon and Google encouraging consumers to include the device on their shopping lists. The trendline from Kagan shows the amazing growth in smart speakers shipments from 2016 -2020.

Despite some supply chain challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic that slowed production in 2020 and 2021, and in some cases, reduced product availability, overall demand for smart speakers has remained robust. As a result, global shipments are projected to increase from 166.2 million units in 2020 to over 186 million in 2021.

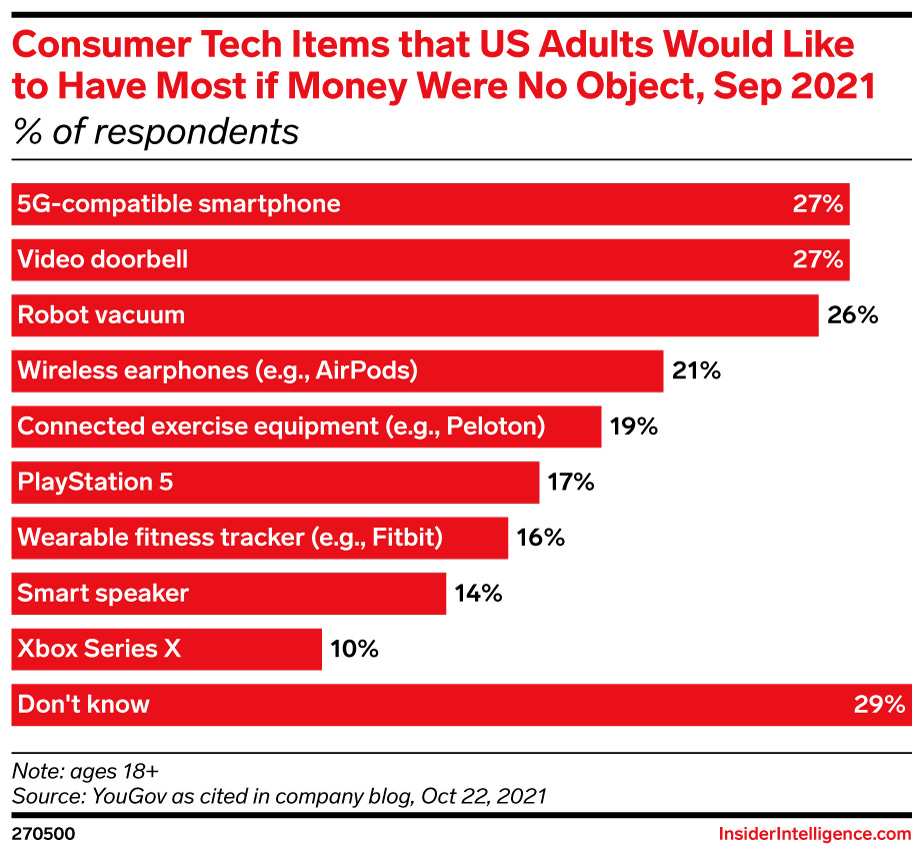

According to a recent YouGov study, it’s also encouraging that these voice-enabled products continue to be among the most sought-after tech items for U.S. consumers.

While smart speakers are not as desired as a robot vacuum or a 5G-compatible smartphone, to have them among the top ten is a positive. This is particularly true since Amazon’s Echo and Google’s Home Nest products are not the shiny new objects as they’ve been around for a few years.

Meanwhile, an interesting thing is happening in the U.K. related to smart speakers and radio.

The website Voicebot.ai is reporting on a British government report suggesting that it may need to regulate the “big three” (Amazon, Google, and Apple) to protect the U.K. radio industry from smart speakers and voice assistants.

The Digital Radio and Audio Review found that the devices and audio services provided by the three tech giants are rapidly becoming the center of gravity for British audio content consumption. This raises fears that the British companies might lose control over how audio is created and distributed in the United Kingdom.

The adoption of smart speakers in the U.K. is higher than in the U.S., as over 38% of U.K. adults owned a smart speaker at the start of 2021. That was up from 30.7% at the beginning of 2020, a 24.5% increase since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The story in Voicebot.ai notes that live radio is still hugely popular in Great Britain despite changes in the media landscape. Even on smart speakers, it accounts for two-thirds of the audio played, and around 6% of all radio listening is done via smart speakers. Furthermore, the government projects that live radio will still make up the majority of audio consumption during the 2030s, albeit almost only in FM form.

As a solution to at least some of the stakeholders’ concerns, the report suggested the government push back any plans to deregulate the FM radio airwaves in 2030 as previously scheduled. Though the AM channels aren’t worth the cost and effort to run, the expected popularity of FM radio makes shutting off the service before 2030 an error.

The report identifies several future risks for U.K. radio and audio in the landscape of increased smart speaker adoption. Since the “big three” have the ability through its products to develop their strategies to leverage their strength in the market, they could:

Charge for access. Online audio platforms have the capability, though they have not yet used this, to charge radio broadcasters, either for carriage or for sharing of listener or performance data about service usage. The platforms could also create specific functionality for those willing to pay to make content more accessible for listeners to find.

Overlaying advertising. Platforms have the means to recognize small gaps between content to identify advertising content. In theory, platforms could sell advertising slots into these gaps or inject adverts into audio streams as YouTube does for video content. The platforms have not yet introduced paid search advertising on radio streams. Still, platforms might seek to monetize voice search in the future, and this could include overlaying advertising across third-party audio streams carried on their audio devices without permission.

Promoting its own services or favored third parties - Platforms can configure the algorithms that control speech activation to favor their own services - an example would be to direct a requester of specific classical music station to their own generic classical music stream/playlist - and require a second or subsequent request to connect to the requested station.

These concerns arise from the device manufacturers’ gatekeeping position, creating competitive imbalances, a significant issue in the government’s report.

The U.K. media environment is considerably different from the U.S., with the BBC still having enormous influence in the country.

The report also addressed how the smart speakers might dilute the branding power of British broadcasters. The BBC’s research found that those listening to the BBC by smart speaker might now know of care that it is a BBC news report. That’s not ideal for a group that relies on license fees and overseas payment to survive. The BBC brand is hugely valuable worldwide, so any tech that divorces its work from its brand could lead to bigger financial problems later on. The report recommended that the government keep investing in the extended BBC ecosystem and start looking at laws to pre-empt anything Amazon or Google might do to overthrow its system.

The Voicebot.ai story closes with a great quote from Rhona Burns, the BBC’s director of operations:

“Radio plays a unique role in people’s lives. This review recognizes that and proposes important steps to keep radio listening strong as audience habits change, ensuring brilliant content is easy to find and access across all platforms. It also challenges the BBC and the whole industry to keep innovating and evolving our audio offer, whilst keeping linear listening alive for the many millions who love it.”

Since it’s doubtful there will be any government intervention to protect the interests of U.S. radio stations, I view the quote from there BBC’s Burns as a rallying cry for the radio industry in America to “keep innovating and evolving our audio offer.”

The full report from the U.K. government is a fascinating read. Its opening paragraph set the tone for the entire document:

Radio is a great British success story. It has evolved to embrace new digital opportunities to maintain its universal appeal to audiences. It has innovated to remain current, vibrant and vital. Alongside a thriving radio market, new online audio formats including on-demand music streaming and podcasts from both existing broadcasters and new entrants have emerged and grown rapidly, bringing increased choice and new habits to the UK’s audio sector.

Here’s the link to read the report.

Finally, today is Veterans Day. Public media had done an admirable job in creating content and community engagement projects on military and veterans’ issues, as detailed on the CPB website.

I’ve always admired the efforts of StoryCorps to bring the stories of Veterans to our audiences, so we’ll end this week with a video produced for Army infantryman Joseph Robertson’s story about a deadly confrontation during World War II that continued to haunt him throughout his life.

Thanks for reading.

The News Platform Fact Sheet was compiled by Associate Director Katerina Eva Matsa and Research Assistant Sarah Naseer.

Digital devices, by definition, include smartphones, computers, or tablets.

The year-over-year comparison saw the use of radio and print as a platform of choice increase slightly in 2021, while digital devices and television dropped incrementally. The most likely reason for this change is the increase in mobility this year from the lockdowns of 2020.

With the increase in newsletters as a unique news platform, I hope that in future studies, Pew will add that as a specific platform since they don’t fit well into the existing categories.