A Three Things Thanksgiving: Looking Back at a Few Public Radio Turkeys

From the Public Impact Group

This was originally published on November 24, 2021. It’s been slightly updated.

Public radio and radio, as an industry, have some great Thanksgiving traditions.

If you’ve worked in (or listened to) public radio for any period of time, you’ve probably experienced Susan Stamberg finding a way to insert Mama Stamberg’s Cranberry Relish Recipe1 into a Morning Edition story sometime before the fourth Thursday of November. This year’s version aired this past Friday morning, where Susan coerced two former members of The Cranberries to join her as a way to slide the recipe into a story.

For music stations, Arlo Guthrie’s “Alice’s Restaurant” has been an annual staple to the Thanksgiving diet for stations, with WXPN in Philadelphia having the tradition of playing all 18 minutes and 34 seconds at noon on Thanksgiving Day.

One of my favorite Thanksgiving traditions is APM’s Turkey Confidential which started with the original host of The Splendid Table Lynne Rossetto Kasper and has continued with Francis Lam behind the microphone.

But, of course, the number one Thanksgiving radio tradition goes back to October 30, 1978. The episode is titled “Turkeys Away,” Thanks to YouTube, the episode’s final act is shared by millions this time of year.

Public radio veteran Ken Mills wrote about the true story that inspired the WKRP episode five years ago on his blog; it’s a fun read.

What occurs to me every time I watch that clip is how what seems to be a great idea sometimes doesn’t work out as planned. Or, as in the case of the WKRP team, they splat in the shopping mall parking lot.

So with the spirit of the best-laid plans that don’t work out, this Thanksgiving edition of the Three Things newsletter is devoted to a few public radio “turkeys” — as in, great ideas that didn’t work out as planned.

Risk, reward, and public radio have a complicated relationship. The same could be said of how public radio looks at failure. Too often, we put our chips into big things hoping for huge results, when often it’s the smaller ideas that end up big.

For the sake of this list, my objective is to not poke fun at people or their ideas, but to look at a few attempts in our industry that just didn’t work out as planned. In fact, some of these ideas were well ahead of their time and may have been a remarkable success in a different moment in history.

THING ONE: Eating Pants… In Five Acts

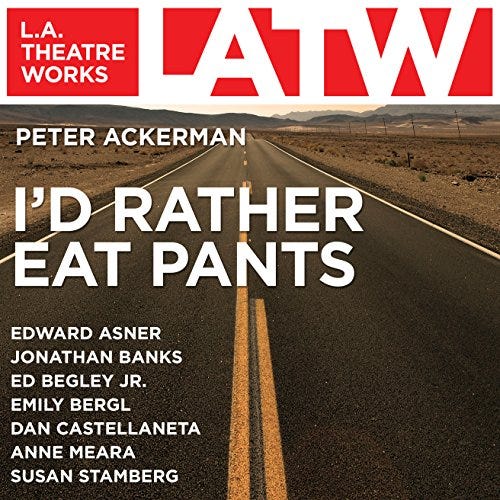

It was about 19 years ago when NPR commissioned a radio play that would run for five consecutive days during Morning Edition in December 2002. The company had just opened NPR West, its production center in Culver City, CA. The idea was to celebrate the opening with a serial radio play featuring some well-known, albeit all-white, Hollywood actors2.

I’d Rather Eat Pants was written by playwright and actor Peter Ackerman, whose debut play, Things You Shouldn’t Say Past Midnight, was performed off-Broadway in New York and at the Soho Rep in London. He came to the attention of NPR because the play was adapted for audio presentation by L.A. Theatre Works and broadcast on many NPR stations.

The play was described as a comic tale of an elderly couple’s cross-country trek on a young slacker’s motorcycle. They’re in search of fame, fortune, and a whole lot more.

You can listen to part one here.3

Sadly, the radio play was not very funny, nor was it well received by Morning Edition listeners at the time.

The Chicago Tribune summarized the listener response to the segments with the headline, NPR listeners would rather eat pants than listen to play.

Host Bob Edwards read some of the avalanche of negative comments on "Pants" on the air during Christmas week. One listener compared the segment to a fly floating in extra virgin olive oil, while another said that radio greats such as Gracie Allen and Jack Benny are spinning in their graves.

A Los Angeles resident wrote: "My daily dilemma is when to blow-dry my hair, since the noise drowns out a few minutes of the always interesting `Morning Edition.' This week, no problem. As soon as `I'd Rather Eat Pants' comes on, I know I can safely do my 'do and not miss a thing." One message from New York sarcastically thanked NPR for the play, saying, "Normally I would stay in bed, but this thing is so horrible it forces me to get up, turn off the radio and begin my day."

In the Chicago Tribune article, Ellen McDonnell, the executive producer of Morning Edition at the time, said that three out of every four of the 1,000 emails received about the segments were negative. She was quoted saying, “It didn’t have as much punch each day as it needed to have. It wasn’t as funny as it needed to be.”

Ellen went on to say that one of the reasons the experiment may not have worked was that it went against the routine that listeners have during the morning, saying, “People were expecting orange juice, and I gave them grapefruit juice or cranberry juice.”

It may have also been that the play was just not very good.

There have been plenty of experiments during Morning Edition that broke the mold of what you usually hear on the program. For example, think about the first time you heard David Sedaris reading his “Santaland Diaries,” which has become a Morning Edition tradition, or the first time you listened to a Planet Money story on business or the economy.

We should learn from this attempt that no matter how many resources you put into something, it’s probably not going to work if it's not very good. And as Ellen said, probably trying this experiment during Morning Edition was perhaps not the best call for this particular radio drama.

But, you know what, to my knowledge, no one at NPR lost their job or was reprimanded for the “Pants” incident, NPR’s audience didn’t tank after the five-day run, and no major funders were lost from the experiment. It was just an idea that didn’t work out as planned, and some lessons were learned -- time to move on.

THING TWO: When a Good Evening Needed to be Great

One of the two most successful weekend franchises in public radio history was A Prairie Home Companion4. It was a program that ended suddenly the first time, at its peak, came back under a different name and from a different location. The program then returned to its origins in name and location and finally attempted to transition to a new host after Garrison Keillor retired in 2017. The end of PHC is well documented, but for this public radio “turkey,” we turn the clock back to the end of the first run of A Prairie Home Companion.

The story goes back to February 1987 when Garrison Keillor stunned listeners and public radio programmers across the country when he announced live on the show, without any advance notice to stations, that the show would be ending with its last show in June of that year.

Minnesota Public Radio moved quickly to fill the hole left behind by Keillor and PHC, announcing a new variety show performed live from the World Theater in Saint Paul5, the same stage that hosted PHC. The show, which debuted in January 1988, was called Good Evening and was hosted by Noah Adams, who left his position as host of All Things Considered to move to Minnesota to, in some ways, fill Garrison’s very large shoes.

A preview story in The New York Times in December 1988 reported that the new show would have a budget of $1.2 million, the equivalent of $2.7 million today, for 39 weekly 90-minute programs.

I had a chance to see the show live in St. Louis during its very short run. The signature element of the show was an essay from Noah titled “St. Croix Notes.” In this show, Noah told the story of driving from St. Paul to St. Louis on the Great River Road. It must have been a terrific essay for me to remember it decades later.

Noah later published his essays from the show in a 1990 book by the same title. Much of the rest of the program was similar to PHC, with music, mostly folk, and attempts at humor.

But it didn’t resonate with listeners who had become incredibly loyal to Keillor and the News from Lake Wobegon. It also was a tough fit for public radio programmers at the time. PHC was a two-hour show. Good Evening was 90 minutes. This made scheduling a challenge as stations had to figure out what 30-minute program would work following the show.

By the fall of 1988, ten months into the first season, Minnesota Public Radio announced that Noah was leaving the show at the end of the year.

″It’s been a wonderful two years here,″ Adams told WCCO-TV of Minneapolis. ″I think of it, in a way, as having left someplace and gone to make a movie for a couple of years and made the movie and it’s worked. And I don’t think they want to make it again for the next two years. I want to find some other movie to make.″

Adams added in an AP story about his departure, “We were pretty sure that good music, literature, and storytelling could be brought together in a live broadcast from the World Theater that would find a substantial and appreciative audience.

″Now we’re convinced of that. I think we’ve established a format that can continue for many years.″

This proved not to be the case.

The show continued for a while into 1989, with an assortment of guest hosts ending later in the year. This coincided with Keillor’s return, announced at the Public Radio Conference in May 1989, that he would be hosting a “new” program called American Radio Company of the Air live from New York City on Saturday evenings beginning that fall6.

There are numerous reasons that Good Evening didn’t work out.

It was too much like PHC but without the personality of Keillor.

The show’s success was made that much more challenging because many stations were also running Best of A Prairie Home Companion programs during their weekend schedule.

The 90-minute show was a tough fit within the program schedule.

It was expensive.

And Keillor decided he wanted to return, ultimately determining the show’s fate.

THING THREE: “Evening is a Time of Real Experimentation. You Never Want to Look the Same Way”

The headline quotes fashion designer Donna Karan and fits our third public radio “turkey.”

Evenings on public radio have traditionally been when news stations might drop some music programming or run repeats of weekend shows. Classical music stations in the past may have scheduled blocks of recorded concerts or stripped Performance Today across each weeknight.

In general, it’s a time when you’re typically not going to invest a lot of resources into whatever you put on the air since the audience is a fraction of the listeners that you have between 6 a.m. and 7 p.m.

But there have been exceptions to this thinking.

The best example in my memory of an ambitious attempt to create something original for public radio in the evenings was the program Heat with John Hockenberry.7

The program had a remarkably talented team working on the show. Steve Rathe of Murray Street Productions created the show with a number of other accomplished producers that included Ira Glass, Joe Richmond, Marika Partridge, and many others8.

Several shows are available on PRX, where the website also tells a little about the program’s beginnings.

In January 1986, General Manager Brad Spear at WGBH suggested a collaboration with Murray Street in contemplation of the newly created CPB radio program funding. Steve Rathe and Leslie Peters worked with Spear and WGBH PD Ellen Kraft, adding music director Bob Telson and others to the team.

In August 1986, Heat of the Night with Marty Goldensohn premiered for two nights on WGBH. The original guest list included: Barbara Ehrenreich, Stanley Aaronowitz, Lionel Tiger, VertaMae Grosvenor, John Pareles, Eric Bogosian, Ellen Goodman. The program subsequently won a Gold Award for programming from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. (But no funding from them.)

In 1988 the NEA Media Program, under the leadership of Brian O'Doherty with David Wolfe, made its largest radio grant that year toward production of Heat. Additional fundraising brought the total to just over half the annual budget and with Wes Horner's encouragement and Peter Pennekamp's activism, NPR committed to providing the balance with the support of the John D and Katherine T. Macarthur Foundation and others.

In February, 1990, Heat with John Hockenberry -- the largest independently produced program in public radio, was premiered on NPR. The producer for the pilots was Ira Glass. Series producer RJ Cutler joined in March.

This brief history didn’t mention that the show aired weeknights at 10 p.m. Eastern time.

That’s not a typo. I did mean to write 10 p.m.

The budget for the show was somewhere between $900,000 to $1.7 million.

In 1990.

For a two-hour program that aired at 10 p.m.

Oh. And of the hundreds of NPR stations that could choose to pick up the program, less than 50 decided to air the show.

With these dynamics at play, the series lasted eight months, from February through September 1990. The Chicago Reader wrote an obituary for the program that month that detailed the last-gasp attempt for the show to acquire CPB funding to save it from extinction. Unfortunately, as Michael Miner snarkily wrote in the piece, it didn’t work out.

For tonight, monitoring the show at Murray Street, was Rick Madden, director of the radio program fund of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Madden controls $4 million in grants. Three times, when Heat was just a proposal, CPB had refused to fund it. Now that the show was on the air everyone was hoping CPB would finally reach into its pockets. Madden came by because Heat is not carried in Washington and he wanted to get a feel for the program. When he disappeared into the night, unimpressed, Rathe had the desperate sense of half a million dollars vanishing with him. A few days later, Rathe and NPR agreed to pull the plug.

In the end, Heat was ignored by most and loved by a few. But those who loved it really loved it. Enough so that it received a George Foster Peabody Award in 1991.

The one thing that can be said about Heat is that it was not predictable. Perhaps that’s a gross understatement.

You can listen to several shows on the PRX site, including an interview with George Carlin and programs that featured performances by Dr. John, bluesman Mose Allison, and South African musician Johnny Clegg.

There’s also a downright wild program featuring Harvard Divinity Professor Harvey Cox guiding listeners through what the end of the world might look like. This same program featured readings by New York actor David Warrilow from T.S. Elliot and the book of Mormon.

I also found two clips on Soundcloud of a program that featured Captain Beefheart band member Gary Clark and singer and writer Nick Cave. It gives you a pretty good taste of what Heat was all about and why it probably didn’t work so well on public radio in 1990.

This is part one.

This is part two.

The program was an experiment that never really had a chance to succeed, given the economics of public radio. So it was kind of like opening an Art House movie theater inside a Chuck E. Cheese.

Perhaps today, some variation of Heat might work as a podcast. However, it was a costly experiment thirty years ago; I find it difficult to think that it would succeed today, given the limited resources across the industry.

All three of these examples had the noblest intentions. But when it came down to it, they didn’t work out.

What I think is important to remember is that many of our successes have come from small ideas that became big things.

Take the idea of the Tiny Desk Concert.

Bob Boilen and Stephen Thompson at NPR started with a small idea in 2008. As of last month, more than 800 concerts in the series have been viewed a collective two billion times on YouTube.

What other examples do you have that might fit into the “turkey” category?

Better yet, what fits into the category of a small idea with huge results, leave a comment with your thoughts.

Thanks for your indulgence with this week’s special Thanksgiving weekend edition of Three Things, and have a Happy Thanksgiving weekend.

“Sounds terrible, tastes terrific.”

The actors included the late Edward Asner, Jonathan Banks (best known today as Mike Ehrmantraut from Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul), Ed Begley, Jr, Dan Castellaneta (the voice of Homer Simpson then and now), the late Ann Meara, Emily Bergl, and Clea Lewis. Bob Edwards and Susan Stamberg also appeared in cameo roles in the radio play.

Obviously, the other was Car Talk.

The World Theater was renamed in 1994, this time for author F. Scott Fitzgerald, a native of Saint Paul.

The “new” show was not necessarily well-received, as detailed in this Washington Post story.

Another may have been Fair Game with Faith Salie, which PRI distributed from 2007 - 2008.

Other producers included Ted Bonnitt, Eileen Delahunty, Ellen Dennis, Donna Gallers, Nick Hill, Brad Klein, Susanna Nicholson, Doris Ung, and Derek Vaillant.